Django Testing Tutorial

Updated

Table of Contents

Testing is an important but often neglected part of any Django project. In this tutorial, we'll review testing best practices and example code that can be applied to any Django app. I also cover testing in depth with many examples in my three books: Django for Beginners, Django for APIs, and Django for Professionals.

Broadly speaking, there are two types of tests you need to run:

- Unit Tests are small, isolated, and focus on one specific function

- Integration Tests are aimed at mimicking user behavior and combine multiple pieces of code and functionality

While we might use a unit test to confirm that the homepage returns an HTTP status code of 200, an integration test could mimic a user's entire registration flow.

For all tests, the expectation is that the result is either expected, unexpected, or an error. An expected result would be an HTTP 200 response on the homepage, but we can--and should--also test that the homepage does not return something unexpected, like an HTTP 404 response. Anything else would be an error requiring further debugging.

The main focus of testing should be unit tests. You can't write too many of them. They are far easier to write, read, and debug than integration tests. They are also quite fast to run.

When to Write/Run Tests

In the words of Django co-creator Jacob Kaplan-Moss, "Code without tests is broken as designed." You should write and run tests all the time. Whenever new code has been added to a project, it is not done until tests are added to confirm it works as intended and doesn't break other project code.

A beginner might think that writing tests takes too long, but tests very quickly save huge amounts of time. Even for a solo developer, projects grow in size. Who knows if that new 3rd party integration works properly or subtly breaks an important part of your site? What if you step away from the code for a few weeks/months and can't remember everything? Or if a colleague needs to make a change?

Tests can be confusing to write initially—hence this tutorial—but practically speaking, the same patterns are used repeatedly.

It is common on many projects to rely on a continuous integration service to automatically run all existing tests on every new commit. This way you don't have to run tests manually.

Initial Set Up

Complete setup instructions can be found here for installing Python, Django, Git, and the rest. In this tutorial we will use the standard Unix prompt of $ to precede all commands.

Assuming you already have Python installed and know how to use the command line, navigate to the Desktop and create a new directory called djangotesty.

# Windows

$ cd onedrive\desktop\code

$ mkdir djangotesty

$ cd djangotesty

# macOS

$ cd ~/desktop/code

$ mkdir djangotesty

$ cd djangotesty

We will create a new virtual environment called .venv and install Django. These instructions place it on the Desktop but any location you can easily access is fine.

# Windows

$ python -m venv .venv

$ .venv\Scripts\Activate.ps1

(.venv) $ python -m pip install django~=5.2.0

# macOS

$ python3 -m venv .venv

$ source .venv/bin/activate

(.venv) $ python3 -m pip install django~=5.2.0

Now create a new Django project called django_project and run migrate to set up the initial database.

(.venv) $ django-admin startproject django_project .

(.venv) $ python manage.py migrate

Run runserver now to confirm everything is installed properly. If you visit http://127.0.0.1:8000/ in your web browser, you should see the following image:

In this tutorial, we will create two apps and test them thoroughly: a pages app with two static pages and a messageboard app with a list view. My book Django for Beginners provides a fuller description of these apps and Django itself. Since the focus here is on testing, I will tersely give the commands to set up each now.

Hello, World and About Page

Let's create a basic home page and about page that we can then test. A fuller description of a Django Hello, World app can be found here. I will tersely give the commands here so we can focus on testing instead.

Create a new app called pages.

(.venv) $ python manage.py startapp pages

Add it to the INSTALLED_APPS configuration within django_project/settings.py.

# django_project/settings.py

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"django.contrib.admin",

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"django.contrib.sessions",

"django.contrib.messages",

"django.contrib.staticfiles",

"pages", # new

]

Ultimately we need dedicated views, urls, and templates for these two pages. We'll start with the views.

Update pages/views.py with two class-based views, HomePageView and AboutPageView, that rely on the corresponding templates home.html and about.html.

# pages/views.py

from django.views.generic import TemplateView

class HomePageView(TemplateView):

template_name = "pages/home.html"

class AboutPageView(TemplateView):

template_name = "pages/about.html"

Create a new file, pages/urls.py, for our two URL paths. We import both views at the top of the file, set them to "" and about/, and provide each with a URL name.

# pages/urls.py

from django.urls import path

from .views import HomePageView, AboutPageView

urlpatterns = [

path("", HomePageView.as_view(), name="home"),

path("about/", AboutPageView.as_view(), name="about"),

]

Update the django_project/urls.py file with our pages app URL paths.

# django_project/urls.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include # new

urlpatterns = [

path("admin/", admin.site.urls),

path("", include("pages.urls")), # new

]

Lastly we need to create the template files for home.html and about.html referenced in pages/views.py. Django will automatically look for a templates/app_name directory within each app, so create that now.

(.venv) $ mkdir pages/templates

(.venv) $ mkdir pages/templates/pages

Then, in your text editor, create pages/templates/pages/home.html and pages/templates/pages/about.html. Fill in the templates with the following simple code.

<!-- pages/templates/pages/home.html -->

<h1>Homepage</h1>

<!-- pages/templates/pages/about.html -->

<h1>About page</h1>

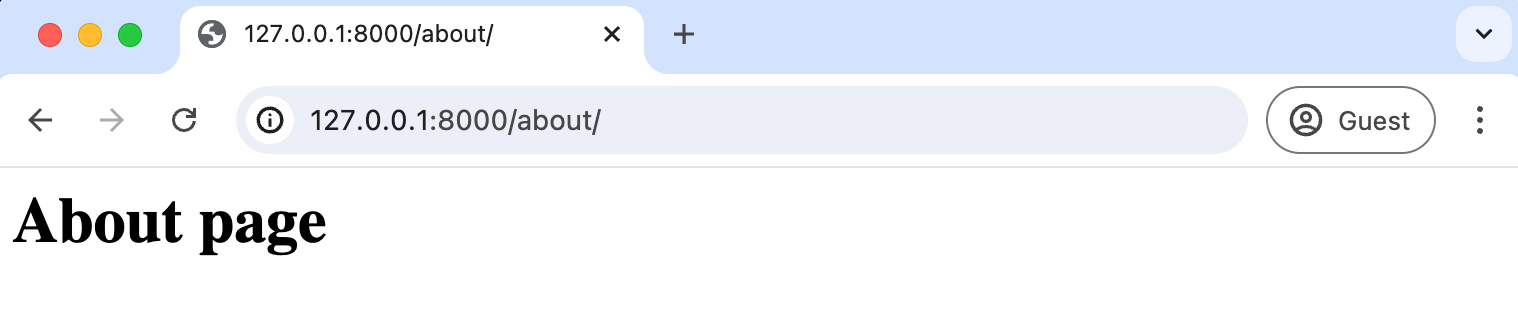

Then navigate to the homepage at http://127.0.0.1:8000/ and about page at http://127.0.0.1:8000/about to confirm everything is working.

Time for tests.

Django Testing

Django comes with a small set of its own tools for writing tests, notably a test client and four provided test case classes. These classes rely on Python's unittest module and TestCase base class.

The Django test client can be used to act like a dummy web browser and check views. This can be done within the Django shell for one-off tests but is more commonly integrated into unit tests.

Most Django unit tests rely on TestCase but on occasions when an application does not rely on a database, SimpleTestCase can be used instead.

SimpleTestCase

Since our pages app currently has only two static pages, we can use SimpleTestCase in the existing pages/tests.py file.

Take a look at the code below which adds four tests for our homepage. First, we test that the URL works correctly and the / web page, the homepage, returns an HTTP 200 Response. Second, we confirm calling the page by its URL name via reverse(). This is why we added name="home" to the pages/urls.py URL path for the homepage. Third, we confirm the template used is home.html. Finally, we check the template's content, looking for the HTML snippet <h1>Homepage</h1> and also that incorrect HTML is not on the page. It's always good to test both expected and unexpected behavior.

# pages/tests.py

from django.test import SimpleTestCase

from django.urls import reverse

class HomepageTests(SimpleTestCase):

def test_url_exists_at_correct_location(self):

response = self.client.get("/")

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_url_available_by_name(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_template_name_correct(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "pages/home.html")

def test_template_content(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertContains(response, "<h1>Homepage</h1>")

self.assertNotContains(response, "Not on the page")

Now run the tests. They should all pass.

(.venv) $ python manage.py test

Found 4 test(s).

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

....

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 4 tests in 0.007s

OK

As an exercise, see if you can add a class for AboutPageTests in this same file. It should have the same five tests but will need to be updated slightly. Run the test runner once complete. The correct code is below so try not to peak...

# pages/tests.py

from django.test import SimpleTestCase

from django.urls import reverse

class HomepageTests(SimpleTestCase):

def test_url_exists_at_correct_location(self):

response = self.client.get("/")

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_url_available_by_name(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_template_name_correct(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "pages/home.html")

def test_template_content(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("home"))

self.assertContains(response, "<h1>Homepage</h1>")

self.assertNotContains(response, "Not on the page")

class AboutPageTests(SimpleTestCase): # new

def test_url_exists_at_correct_location(self):

response = self.client.get("/about/")

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_url_available_by_name(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("about"))

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_template_name_correct(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("about"))

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "pages/about.html")

def test_template_content(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("about"))

self.assertContains(response, "<h1>About page</h1>")

self.assertNotContains(response, "Should not be here!")

Run the new tests now.

(.venv) $ python manage.py test

Found 8 test(s).

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

........

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 8 tests in 0.008s

OK

There are many more tests we could conceivably add but for static webpages these tests cover the basics: validating an HTTP 200 response, the correct view and template are used, and checking the template's content.

Message Board App

Now let's create our message board app so we can try testing out database queries. First create a new app called posts.

(.venv) $ python manage.py startapp posts

Add it to the django_project/settings.py file.

INSTALLED_APPS = [

"django.contrib.admin",

"django.contrib.auth",

"django.contrib.contenttypes",

"django.contrib.sessions",

"django.contrib.messages",

"django.contrib.staticfiles",

"pages",

"posts", # new

]

Now add a basic model.

# posts/models.py

from django.db import models

class Post(models.Model):

text = models.TextField()

def __str__(self):

"""A string representation of the model."""

return self.text

Create a database migration file.

(.venv) $ python manage.py makemigrations

Migrations for 'posts':

posts/migrations/0001_initial.py

- Create model Post

And then apply it to the database with migrate.

(.venv) $ python manage.py migrate

Operations to perform:

Apply all migrations: admin, auth, contenttypes, posts, sessions

Running migrations:

Applying posts.0001_initial... OK

For simplicity we can just a post via the Django admin. So first create a superuser account and fill in all prompts.

(.venv) $ python manage.py createsuperuser

Update our admin.py file so the posts app is active in the Django admin.

# posts/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from .models import Post

admin.site.register(Post)

Then restart the Django server with python manage.py runserver and login to the Django admin at http://127.0.0.1:8000/admin/. You should see the admin’s login screen:

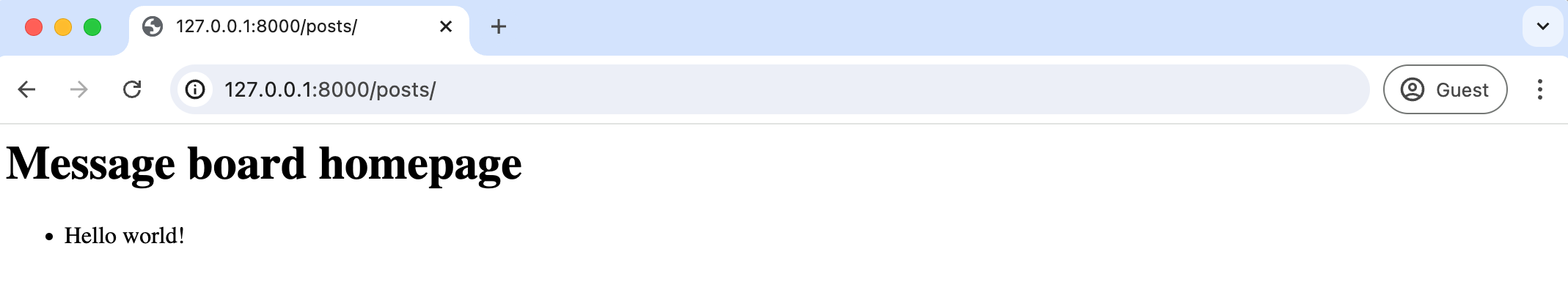

Click on the link for + Add next to Posts. Enter in the simple text Hello world!.

After pressing the "save" button you'll see the following page.

Now add our posts/views.py file.

# posts/views.py

from django.views.generic import ListView

from .models import Post

class PostPageView(ListView):

model = Post

template_name = "posts/posts.html"

Create directories for posts/templates and posts/templates/posts. Then add a posts/templates/posts/posts.html template file in your text editor and include the code below to simply output all posts in the database.

<!-- posts/templates/posts/posts.html -->

<h1>Message board homepage</h1>

<ul>

{% for post in object_list %}

<li>{{ post.text }}</li>

{% endfor %}

</ul>

Update our urls.py files. Start with the project-level one located at django_project/urls.py.

# django_project/urls.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.urls import path, include

urlpatterns = [

path("", include("pages.urls")),

path("admin/", admin.site.urls),

path("posts/", include("posts.urls")),

]

Then create a posts/urls.py file in your text editor and populate it as follows.

# posts/urls.py

from django.urls import path

from .views import PostPageView

urlpatterns = [

path("", PostPageView.as_view(), name="posts"),

]

Okay, phew! We're done. Start up the local server python manage.py runserver and navigate to our new message board page at http://127.0.0.1:8000/posts.

It simply displays our single post entry. Time for tests!

TestCase

TestCase is the most common class for writing tests in Django. It allows us to mock queries to the database.

setUpTestData() lets us create initial data once, at the class level, for the entire TestCase. This technique allows for much faster tests than creating the data from scratch for each individual unit test within the class.

Let's test out our Post database model.

# posts/tests.py

from django.test import TestCase

from django.urls import reverse

from .models import Post

class PostTests(TestCase):

@classmethod

def setUpTestData(cls):

cls.post = Post.objects.create(text="This is a test!")

def test_model_content(self):

self.assertEqual(self.post.text, "This is a test!")

def test_url_exists_at_correct_location(self):

response = self.client.get("/posts/")

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

def test_homepage(self):

response = self.client.get(reverse("posts"))

self.assertEqual(response.status_code, 200)

self.assertTemplateUsed(response, "posts/posts.html")

self.assertContains(response, "This is a test!")

The first unit test, test_model_content, checks that the data in our mock database matches what was initially created in setUpTestData. Then we check the URL to confirm it returns an HTTP 200 Response. And finally test_homepage uses reverse to call the URL name, checks for an HTTP 200 Response, verifies the correct template is used, and confirms that HTML content matches what is expected.

We can run tests on a project-wide basis or specify a more granular approach, such as per-app by adding the app name to the end. Let's test just these three new tests in the posts app.

(.venv) $ python manage.py test posts

Found 3 test(s).

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

...

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 3 tests in 0.008s

OK

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Now run all our project's tests which will include both the pages app and the posts app.

(.venv) $ python manage.py test

Found 11 test(s).

Creating test database for alias 'default'...

System check identified no issues (0 silenced).

...........

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 11 tests in 0.012s

OK

Destroying test database for alias 'default'...

Test Layout

As Django projects grow in complexity, it is common to delete the initial app/tests.py file and replace it with an app-level tests folder that contains individual tests files for each area of functionality. Therefore instead of a single pages/tests.py file you could have a pages/tests/ directory and within it decided files--all starting with test_--for different areas of the app.

|__pages

|__tests

|-- __init__.py

|-- test_forms.py

|-- test_models.py

|-- test_views.py

We don't have anywhere near enough tests yet for this refactoring to make sense but as a project expands further dividing the tests in this fashion can help reason about the code.

Next Steps

There is far more testing-wise that can be added to a Django project. A short list includes:

- Continuous Integration: automatically run all tests whenever a new commit is made, which can be done using Github Actions.

- pytest: pytest is the most popular enhancement to Django and Python's built-in testing tools, allowing for more repeatable tests and a heavy use of fixtures.

- coverage: With coverage.py you can have a rough overview of a project's total test coverage.

- Integration tests: useful for testing the flow of a website, such as authentication or perhaps even payments that rely on a 3rd party.

All three of my books on Django contain comprehensive testing so if you're interested in learning more about Django testing, they are a good resource (and the first several chapters of each can be read for free online):

I also recommend Adam Johnson's book, Speed Up Your Django Tests, which is a more advanced but excellent guide to tests.